Key Takeaways:

· Fast cash; may lead to lasting damage: Unilateral rewrites boost headline revenue quickly but impose the heaviest long-term costs through project delays, arbitration payouts, and collapsed exploration.

· Renegotiation works—if swift: Incremental or dispute settlement adjustments can raise state take without scaring off capital, but protracted talks erode project value.

· Future only resets preserve credibility: Applying new fiscal terms solely to fresh acreage limits downside risk. Success hinges on the competitiveness of new terms.

Governments in hydrocarbon economies are often tempted to revisit current or legacy oil and gas contracts to raise revenue, especially in emerging or frontier basins. Active talks in Kazakhstan, Tanzania, and Senegal are only the latest attempts to rebalance production‑sharing terms and capture more rent. History, however, shows that quick fiscal wins can often carry significant risks and consequences: project timelines slip, foreign capital retreats, arbitration costs mount, and future tax receipts suffer, depriving local economies of broader benefits.

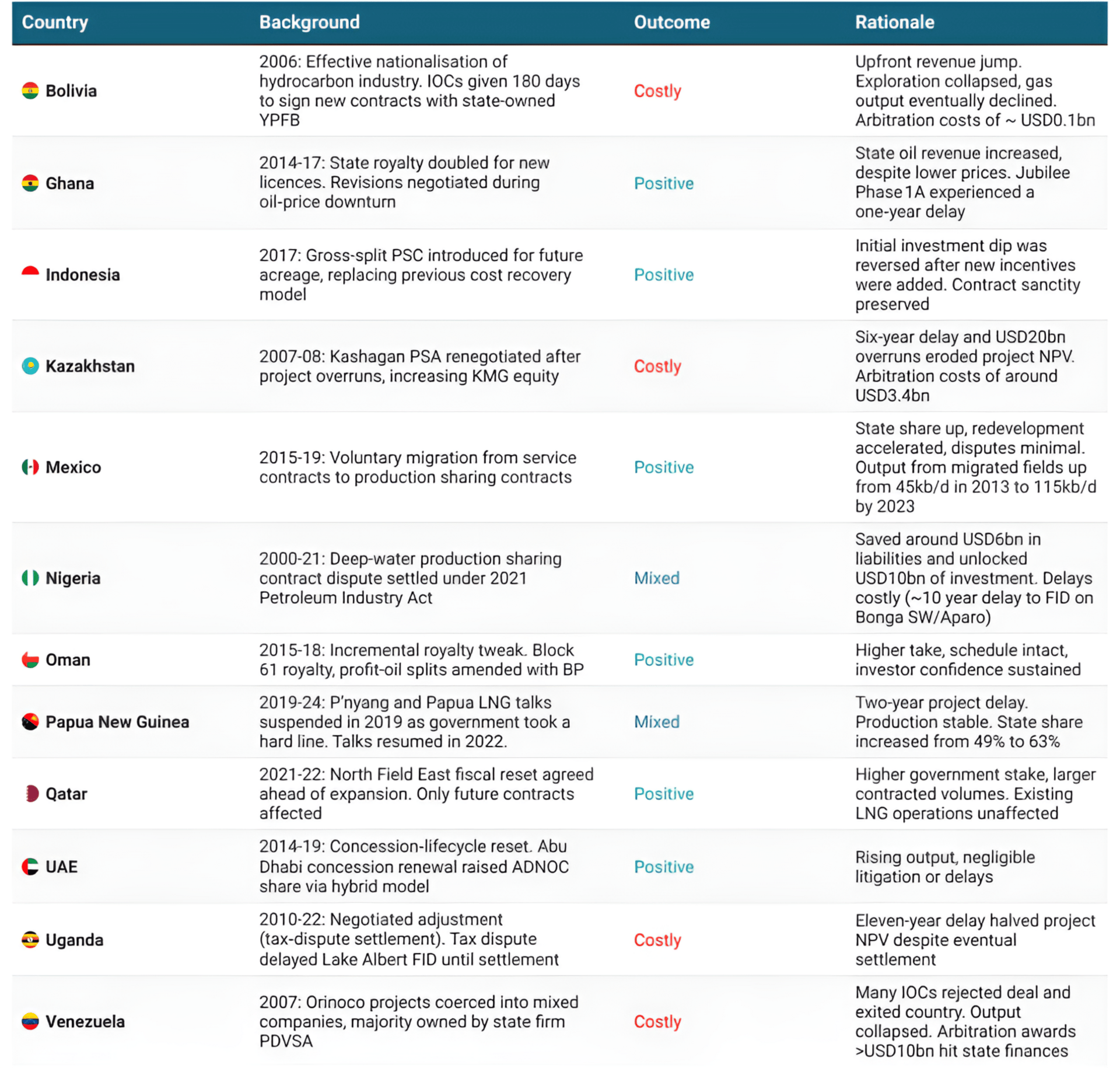

This article applies a targeted, cross-regional lens, to a comparison of twelve high-profile renegotiations across Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, and the Asia-Pacific region. Cases range from Bolivia’s hydrocarbons nationalization 1to Papua New Guinea’s royalty hike, 2and fall into three playbooks: coercive retroactive grabs, negotiated adjustments, and forward‑looking regime resets.

Our analysis unearths three distinct themes, outlined at the beginning of this article. Understanding these trade‑offs is essential for policy makers seeking higher fiscal shares without sacrificing the contract credibility that anchors future investment.

Figure 1 - Twelve High Profile Oil & Gas Contract Revision Case Studies

Source: Company and news reports, Guyana Economic Monitor

Key Drivers of Contract Renegotiations

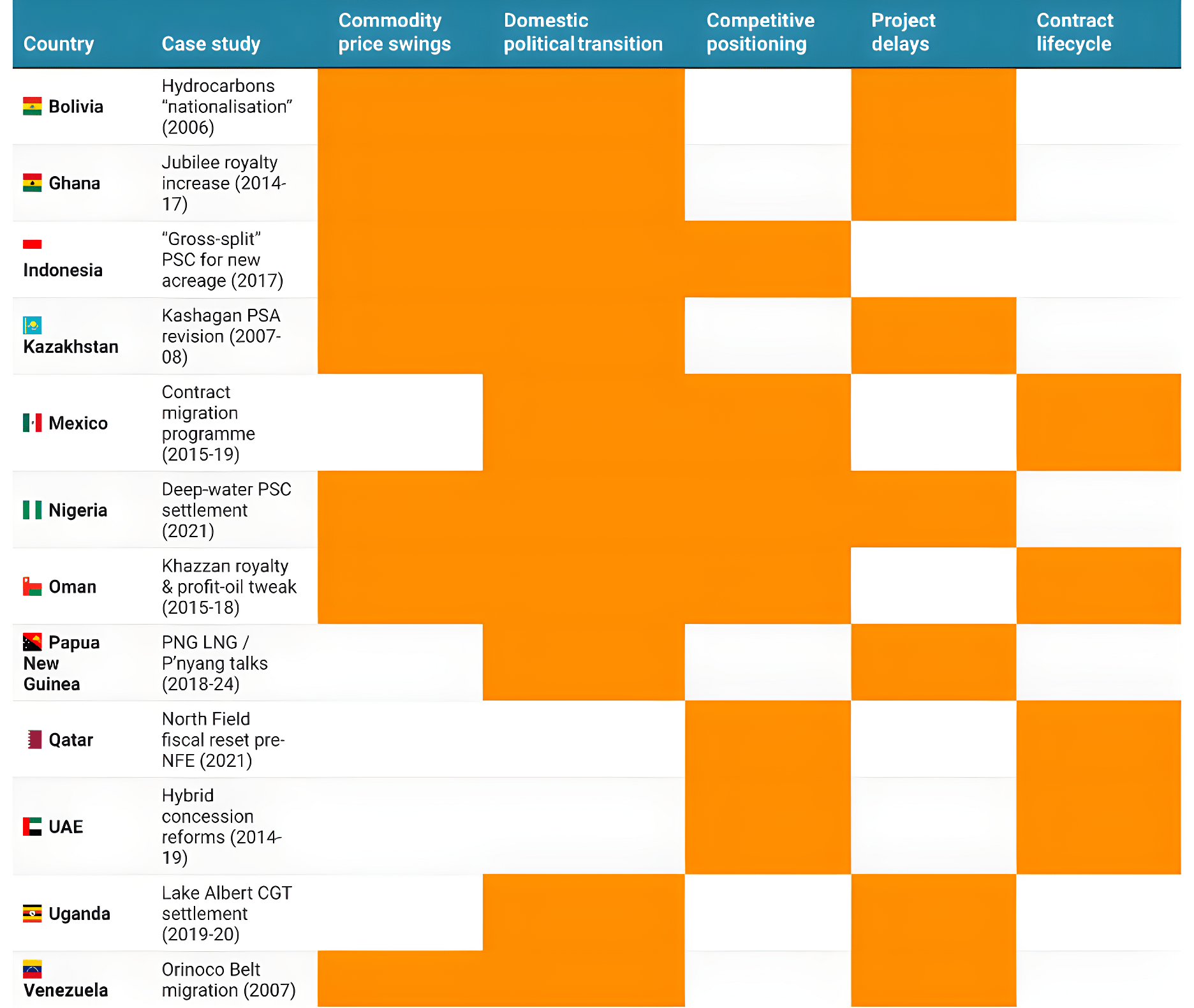

Research indicates five recurring factors explain why governments reopen upstream contracts. Some are external factors, such as commodity price swings and shifting international norms, while others are country-specific, including political transitions and project underperformance:

Commodity price swings: Surging oil and gas prices often encourage the state to increase its take (Bolivia, Venezuela). Sharp price downturns, such as the 2015-16 oil price slump, pressure treasuries to revisit terms to plug budget shortfalls (Oman, Ghana). A commodity price swing contributed to eight of the twelve case studies in this article.

Domestic political transition: Renegotiation often follows elections contested on resource-nationalist platforms, or amid concerns over corruption and inequality. New administrations seek visible wins by revising legacy deals. These political pressures contributed to ten of the case studies, whether through populist mandates (Bolivia, PNG) 3or explicit treasury needs (Nigeria).4

Competitive positioning: Contract changes often arise when neighboring jurisdictions secure more investment-efficient terms, prompting governments to update their regulatory frameworks (Mexico, Qatar, UAE). Governments can also be encouraged to increase their take if regional peers are deemed to have recently secured more favorable deals

Project delays and underperformance: Persistent cost overruns, deferred final investment decisions (FIDs), and repeated schedule slippages often create the conditions for renegotiation. Governments typically respond by asserting greater control or pressing for more favorable terms. These government dynamics were key drivers of contract revisions in Kazakhstan 5and Uganda.6

Contract lifecycle: The expiry of long-dated concessions or license extentions creates a window to recalibrate fiscal sharing without breaching contract sancitity. These contract lifecycle events contributed to four of the twelve case studies, including Qatar and Oman.

Figure 2 - Drivers of Contract Renegotiation

Note: Orange square indicates that the driver was present in that case study Source: Company and news reports, Guyana Economic Monitor

Three Playbooks for Contract Revision

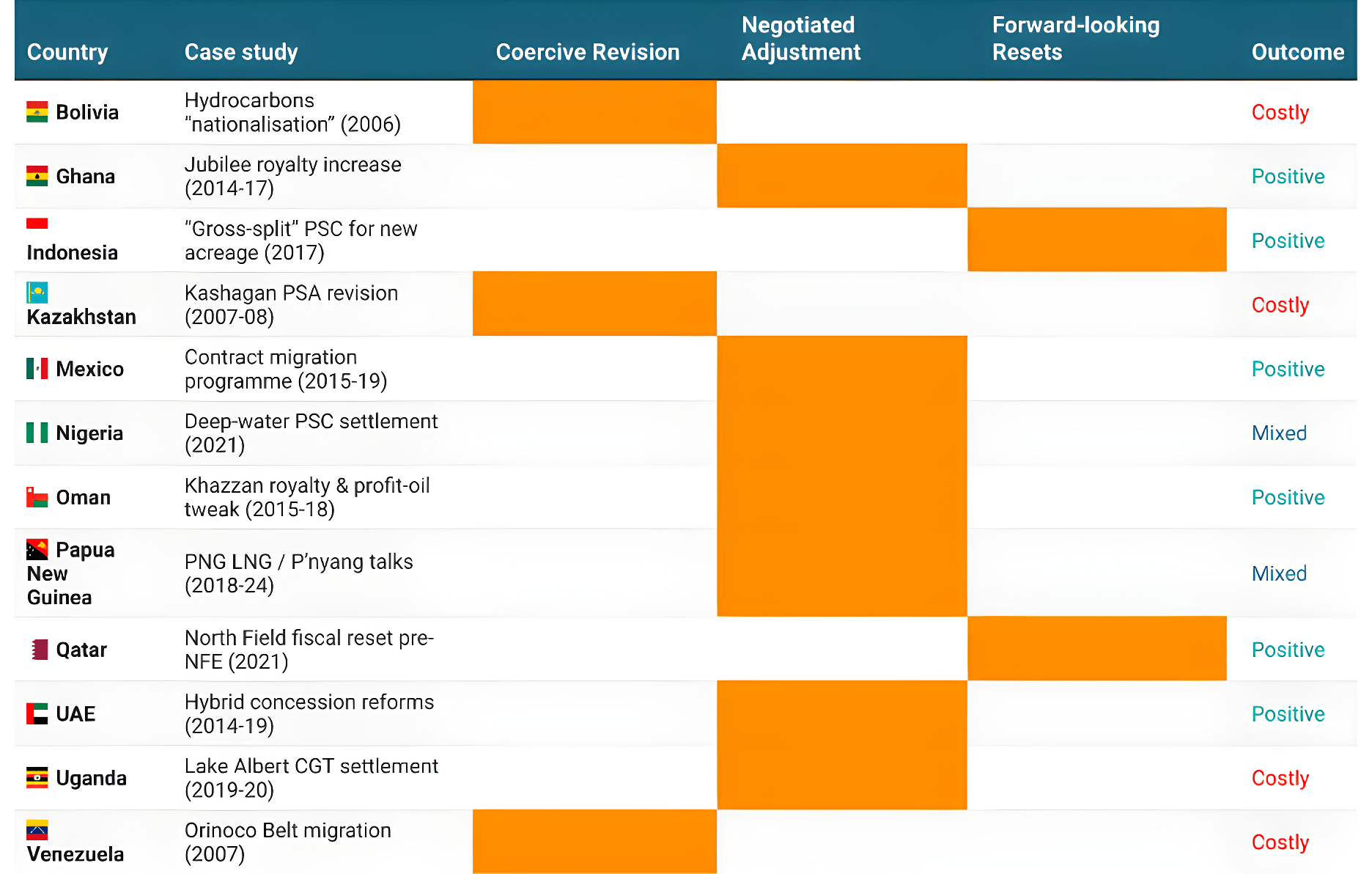

We have grouped the twelve case studies into three distinct playbooks, allowing us to identify common themes and outcomes:

1. Coercive retroactive revision, exemplified by Bolivia, Kazakhstan, and Venezuela, is executed through sudden, top-down legal measures that reopen previously signed contracts. Governments enact new laws or decrees to override stabilization clauses, compel majority transfer to the NOC, hike royalties, levy windfall taxes, and threaten license cancellation, with minimal consultation or compensation.

2. Negotiated adjustments dominate the sample, ranging from hard-line bargaining to collaborative fine-tuning. In these examples, each government stayed within stabilization clauses, settling tax or cost-recovery disputes or making contract revisions in exchange for license offsets. Dialogue limited investor flight, though prolonged talks still deferred revenues. PNG, and to a lesser degree Ghana, sit at the firm end: Port Moresby briefly froze LNG talks in 2019 and lifted state take above 60%, causing a two-year FID slip,7 while Ghana’s royalty hike for new blocks created only a short delay in the Jubilee Project. Oman and the UAE sit at the more cooperative end of the continuum, with new terms increasing the state share without disturbing schedules or exploration appetite. In all cases, negotiation speed impacted long-term value at least as much as headline terms.

Figure 3 - Negotiation Speed is Critical

Note: Delay refers to the number of years by which a major approval, FID, or project phase was postponed due to renegotiation. Source: Company and news reports, Guyana Economic Monitor

3. Forward-looking resets, create a clean fiscal slate without reopening signed contracts. Indonesia’s 2017 switch from cost-recovery to gross-split PSAs eliminated reimbursement audits and generated state revenue from the first production. After investment dipped in 2018, Jakarta added incentives in 2020 to revive bidding. Qatar followed a similar path for the 2021-22 North Field East expansion: legacy LNG trains kept their terms, while new capacity now operates under a quasi-PSC in which QatarEnergy holds a dominant stake and partners accept smaller equity in exchange for tax relief. This contractual ring-fencing leaves existing deals intact, while new acreage terms reflect lower geological risk and stronger state capacity. Investors can participate or walk away without fearing retroactive change.

Figure 4 - Contract Renegotiation Approaches

Note: Orange square indicates that the approach was used in that case study. Source: Company and news reports, Guyana Economic Monitor

Lessons for Policymakers

The central question facing new producers and reform-minded governments is: Can we improve state benefits without triggering investor flight or project delays? Through the above comparative analysis, this article suggests that the following lessons can be taken from high-profile contract revisions:

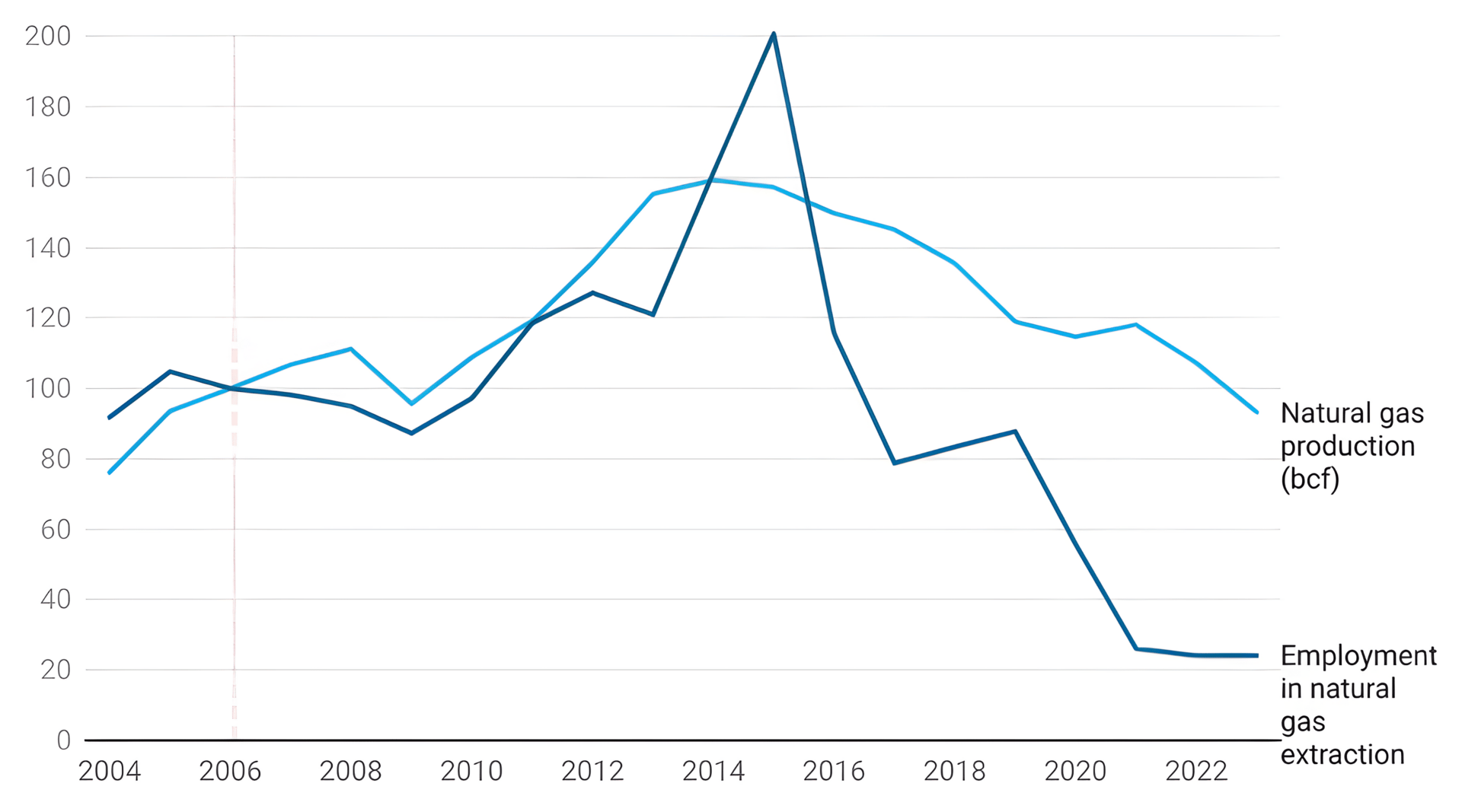

Coercive revenue grabs often erode long-term gains: A comparative review of the twelve case studies reveals a consistent trade-off between short-term and long-term gains. Coercive, retroactive revisions deliver the most visible short-term fiscal uplift - Bolivia, Kazakhstan, and Venezuela extracted double-digit percentage-point increases in headline state take within months. Yet these cases also record the steepest long-term penalties: multi-year project delays, arbitration awards exceeding USD $10 billion (Venezuela) 8and, most critically, a collapse in follow-up exploration that undermined future production and economic benefits for the local economy, especially local suppliers and workers. For instance, Bolivia’s natural gas production (-6.7%) 9and employment (-75.9%) 10were lower in 2023 than they were when the industry was nationalized in 2006 (see chart).

Figure 5 - Bolivia’s Output and Employment Reversal

Dry Natural Gas Production (Bcf) and Employment, Rebased to Year of Nationalization (2006 = 100)

Note: Bolivia’s National Statistics Institute (INE), EIA, Guyana Economic Monitor

Flexible negotiation typically preserves long-term. Negotiated adjustments whether proactive (Oman, UAE, Mexico) or dispute-driven (Uganda) - sit at the midpoint of the short-term gain/long-term value continuum. Royalty tweaks and settlement packages tend to gradually lift state revenue while keeping existing production online. Execution speed, however, is critical. Uganda’s decade-long tax dispute drained net present value despite its eventual settlement. In contrast, Papua New Guinea’s harder but faster approach tells a different story: the government froze talks on Papua LNG and P’nyang in 2019 and concluded a revised gas agreement and fiscal stability agreement within about two years. Production at the existing PNG LNG trains continued uninterrupted, and the project delay was just two years.11

A forward-looking regime resets the limit on both gains and risks. Prospective systemic overhauls (Indonesia, Qatar) minimize retroactive risk by applying new fiscal models only to future acreage. Thier short-term revenue impact is muted, but they retain contract credibility and allow host states to reset terms in line with competitive benchmarks. Success depends on whether the revamped regime still offers investors an adequate post-tax return.

Figure 6 - Hidden Fiscal Costs

Arbitration Awards and Settlements Linked to Renegotiation Episodes (USDbn)

Note: ICSD, Company reports, Guyana Economic Monitor

1 Bolivian President Nationalizes Hydrocarbons Sector, S7P Global, 2006

2 Tiny Pacific island Nation battles oil giant for LNG profis, World Oil, 2018

3 Bolivia’s Nationalization of Oil and Gas, Council on Foreign Relations, 2006

4 NNPC, PSC partners move to boost Nigeria’s oil output from Bonga field, Mediatracnet, 2021

5 Eni loses Kashagan lead role, Kazakhstan ups stake, Reuters, 2008

6 Disputes and delays: Uganda’s long road to first oil, Africa B

7 PNG PM’s big hopes for delapyed LNG project, the Australian Financial Review, 2024

8 ICSID tribunal awards Conoco Philips USD 8.7 billion plus interst in dispute with Venezuela, IISD, 2019

9 US Energy Information Administration, 2025

10 Bolivia National Statistics Institute (INE), 2025

11 Total and the State of Papua New Guinea sign Gas Agreement for Papua LNG project, TotalEnergies, 2019

The information provided in this article is based on the best available sources and is intended for informational purposes only. Due to the dynamic nature of business intelligence, predictions, and analysis, there are inherent risks, including potential inaccuracies, omissions, or delays. All content in this article are provided ‘as is’ and ‘as available,’ without warranties of any kind, express or implied, including but not limited to accuracy, completeness, timeliness, or fitness for a particular purpose. Predictions and analysis involve risks and uncertainties, and we do not guarantee the reliability of the information. By accessing or using this publication, you acknowledge these risks and agree that we, our affiliates, our agents, and contributors shall not be held liable for any decisions made or actions taken in reliance on the content, nor for any direct, indirect, consequential, or special damages arising therefrom, resulting from your reliance on the information provided.