A Strategic Crossroads for Guyana’s Gas Resources

Guyana faces a pivotal decision over how to use its growing natural gas endowment. Significant volumes, comprised of associated gas from producing oil fields, and undeveloped oil discoveries that also contain gas and condensate, could either be exported as LNG or brought onshore to fuel domestic power generation and industrial development. The choice will determine whether Guyana’s hydrocarbon expansion remains an extractive boom or becomes the backbone of broader industrial and fiscal transformation.

To date, only the associated gas from the Stabroek Block’s producing fields (Liza Phase 1 & 2, Payara) has a defined pathway. It is to be transported onshore via a 225 km pipeline, mechanically complete as of October 2024, to supply the Wales Gas-to-Energy project, which comprises a 300MW combined-cycle power plant and an integrated natural gas liquids (NGL) facility.1 Beyond this, Guyana’s remaining gas resources are uncommitted, presenting both opportunity and risk.

Policymakers and investors must now decide how best to use these future gas supplies:

Keep them offshore and export as LNG - generating near-term revenue but more limited domestic multipliers and benefits; or

Bring them onshore to underpin power generation and catalyze new industries, offering longer-term economic, social, and environmental benefits. This second pathway could extend beyond the current Wales project, with Region 6 (East Berbice–Corentyne) emerging as a logical location for future gas-to-energy infrastructure given its proximity to the south-eastern offshore discoveries within the Stabroek block.

While both options could, in theory, proceed in parallel, this would depend largely on the scale of recoverable gas and the government’s capacity to manage two distinct policy and pricing frameworks. Developing both offshore LNG exports, and an onshore gas-to-industry chain, would require separate infrastructure, markets, and investors—potentially diluting focus and limiting economies of scale. In practice, prioritizing one pathway is likely to deliver stronger outcomes in terms of coordination, financing, and national value capture. Recent comments from ExxonMobil Guyana’s president support this logic,2 as they noted that while LNG remains an option for the longer term, the current emphasis is on supplying gas onshore to support power generation and industrial growth.

The Offshore LNG Path: Potentially Faster Returns, But Limited Long-term Social Benefits or Multipliers

Exporting Guyana’s gas as LNG could deliver near-term fiscal and export revenues by allowing production to be monetized offshore, without the need to sychronize with the completion of domestic pipelines, power plants, or industrial facilities. Given Guyana’s deepwater setting and lack of onshore liquefaction infrastructure, LNG exports would almost certainly rely on a floating LNG (FLNG) solution. FLNG enables gas to be processed, liquefied, and stored directly at sea, avoiding extensive onshore construction and long export pipelines. This approach can reduce land acquisition and environmental impacts while lowering upfront capital requirements and shortening time-to-market.3

Yet, this apparent simplicity comes with conditions. Project success would hinge on sufficient quantities of gas to justify such large capital commitments that will be competitive in the global market and securing a technically experienced and financially robust LNG developer with established engineering partners. Without such a lead sponsor, the project could face financing challenges and heightened cost risks. Attracting a reputable, bankable LNG company will also depend on a transparent procurement process from the government—ideally through a dedicated, LNG-specific request for proposals (RFP). Having issued a broad gas-monetization RFP, and identified LNG as a potentially viable pathway, the government should now take a more targeted approach—issuing a dedicated, LNG-specific tender to attract top-tier developers, benefit from price optionality and competition, and ensure clear, bankable proposals, should it choose to pursue this option further.

Mozambique provides a useful example of both the potential and limits of offshore LNG exports. The country’s Coral South FLNG project was relatively quick to build, reaching first cargo in 2022, just five years after its final investment decision, but its wider economic multipliers have been limited. Although a small share of gas is reserved for domestic use, most output is exported. Eni reports that the project has created around 1,400 jobs, invested USD33 million in training, and awarded USD800 million in contracts to Mozambican SMEs important local benefits, yet far short of deep industrial transformation.4 Similarly, the International Institute for Sustainable Development warns that Mozambique’s LNG ventures risk limited domestic value-chain participation, noting that much of the profit and decision control remains concentrated with foreign companies.5

Offshore LNG may therefore offer a viable near-term revenue stream, but not the foundation for Guyana’s broader industrial development and associated social multipliers. Beyond these project-level considerations, the case for offshore LNG will also depend on global market dynamics. According to the IEA’s Gas 2025 report, global LNG supply is entering an unprecedented expansion phase, with around 300 bcm of new export capacity expected by 2030—driven mainly by projects in the United States and Qatar.6 This surge will strengthen supply security but is also likely to push prices lower after the mid-2020s, intensifying competition among producers. In such an environment, investors tend to prioritize large, established exporters with secured offtake agreements, meaning smaller new entrants often need fiscal or contractual incentives to attract financing. Should Guyana pursue LNG in the future, maintaining a transparent and well-structured investment framework will be essential to ensure project bankability while safeguarding long-term fiscal value.

Figure 1: Global Natural Gas Price Index and Indonesian LNG Price,

US$/mn BTU

Note: * Includes European, Japanese, and American Natural Gas Price Indices;

f = forecast. Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, April 2025

The Onshore Gas-to-Industry Path: The Transformative Approach

While LNG exports could generate near-term revenue, the alternative path, bringing gas onshore, arguably offers a more transformative prospect. Onshore utilization would integrate gas into Guyana’s domestic economy, providing feedstock for the power sector and industries, creating infrastructure linkages, and unlocking longer-term economic, social, and environmental benefits.

Power-Sector Transformation

The strongest immediate case for bringing additional gas onshore lies in its potential to strengthen Guyana’s power system, particularly in Region 6. Region 6 sits at the far terminus of the Demerara–Berbice Interconnected System (DBIS)— over 150 kilometers from Georgetown, where most of the country’s installed generation capacity is located. Total DBIS losses reached about 23% in 2022, with reliability problems most acute in outlying areas such as Berbice, where long transmission distances and aging lines heighten vulnerability.7 Strengthening supply in Region 6 through local gas-fired generation would ease pressure on the grid network and improve system stability for communities extending east toward Corriverton and the Suriname border.

Local generation in Region 6, like much of Guyana, relies primarily on heavy fuel oil (HFO). The region’s main supply comes from HFO-fired plants, including the 36MW floating powership at Everton, which was connected to the grid in 2024.8 This dependence on imported liquid fuels contributes to Guyana’s high national electricity costs: average electricity prices are around USD0.32/kWh, among the highest in the region.9 Expanding the use of domestic gas would reduce generation costs, improve supply reliability, and strengthen national energy security by lowering reliance on imported fuels.

Figure 2: Guyana – Total Imports of Refined Oil Fuel, USD million

Source: ITC Trade Map

Developing a gas-to-industry facility in Region 6 would directly address these constraints by generating power closer to demand and reducing reliance on long-distance power transfers from Georgetown. The government’s ongoing transmission-upgrade program, including new 230 kV and 69 kV lines extending eastward from Wales, will strengthen electricity delivery to Berbice but will not remove the region’s dependence on imported fuel. A local gas node would therefore complement these upgrades, providing a reliable and lower-cost anchor for the eastern end of the grid.

Industrial Diversification and Infrastructure Multipliers

Bringing gas onshore would provide the foundation for broad-based industrial and value-added growth across Guyana, supplying both affordable power and feedstock for downstream production. Reliable gas-based energy would lower electricity costs for manufacturing and agro-processing while also supporting energy-intensive industries such as bauxite mining and refining, cement production, and data-center operations. The expansion of AI and cloud computing is driving a global surge in electricity demand from data centers — the IEA projects that global electricity demand from data centers, AI, and cryptocurrency could double between 2022 and 2026, reaching roughly 1,000 TWh — underscoring the strategic value of stable, low-cost power in attracting digital investment.10 At the same time, processed gas could support the production of fertilizer, methanol, and petrochemicals for domestic use and export. Together, these applications would create new markets for local enterprises, reduce reliance on imported fuels and fertilizers, and strengthen Guyana’s industrial base.

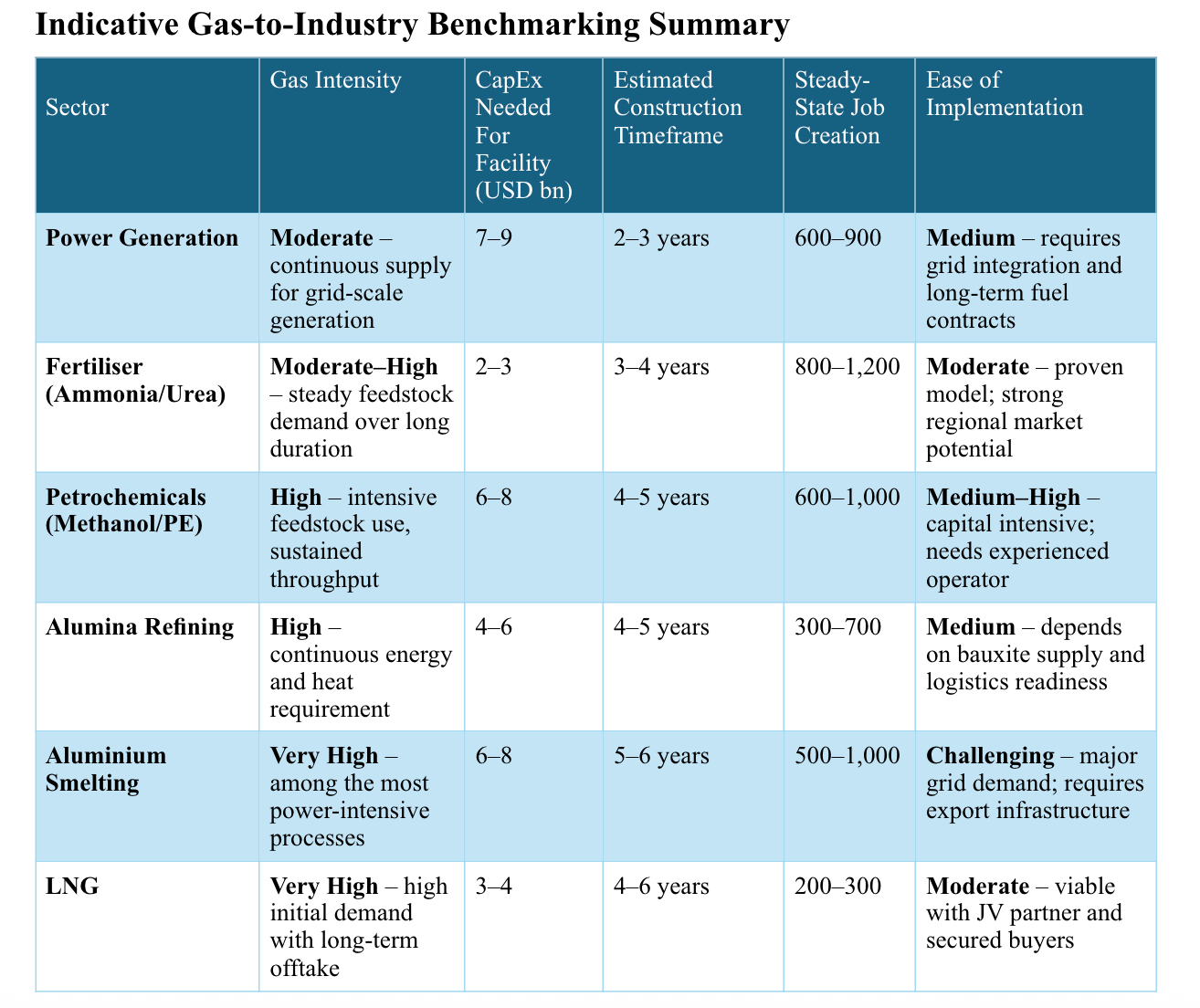

Figure 3: Indicative Gas-to-Industry Benchmarking Summary

Note: These estimates are derived from internal benchmarking of recent gas-industrialization projects in emerging markets and adjusted for Guyana’s scale and development context. Figures are illustrative only and intended to indicate order-of-magnitude requirements for potential project planning rather than precise forecasts.

The Berbice region provides a strategic location for this next phase of development. It sits at the center of several major transport and logistics projects that are set to reshape Guyana’s connectivity: the government-led deep-water port at Berbice, now in the design-finalization stage in partnership with Bechtel;11 the proposed Corentyne River bridge linking Guyana and Suriname;12 and the Linden–Lethem corridor to northern Brazil and new economic trade zone.13 Locating a gas-to-industry and processing complex within this corridor would capitalize on these emerging links, turning Berbice’s infrastructure expansion into a platform for industrial investment. Cheaper, more reliable energy would improve competitiveness across manufacturing, mining, and agriculture, and invite the establishment of new industries such as data centers, while the new port and road network would enable export-oriented industries to access regional markets efficiently.

Brazil, for example, imports roughly 80% of its fertilizer needs, mostly gas-based products such as urea, with volumes rising to nearly 45mn tonnes in 2024.14 Much of this supply comes from Russia and the Middle East, leaving Brazil exposed to long trans-Atlantic shipping routes and geopolitical interruptions.

By leveraging domestic gas and proximity through Berbice’s deep-water port, Guyana could offer shorter, lower-cost supply routes, positioning itself as a competitive new regional supplier. These synergies align with the Government of Guyana’s diversification agenda, using gas infrastructure as the backbone for manufacturing, trade integration, and long-term economic resilience.

Figure 4: Brazil Total Fertilizer Imports, mn tons

Source: ITC Trade Map

Employment and the Social Dimension

Building onshore gas infrastructure and industrial facilities would generate substantial employment during construction and lasting technical and service roles in operation. Unemployment in Guyana at the start of 2021 stood at 15.6 %, with joblessness highest among rural workers and women.15 This labour slack, particularly outside Georgetown, underscores the need for large, regionally distributed projects capable of generating both construction and long-term operating jobs.

In Region 6, where non-farm employment is limited and out-migration has followed the contraction of the sugar industry, the closure of four major estates by the previous APNU/AFC administration (2016–2017) caused significant job losses and reduced household incomes.16 Although the current government is working to revitalize the sector, a gas-to-industry development could help absorb idle and semi-skilled labour, diversify the local economy, and create new supply-chain opportunities for local SMEs.

Sustainable Finance and ESG Opportunities

By replacing diesel and heavy fuel oil in power generation—and supplying lower-carbon feedstock for industries such as fertilizer and petrochemicals—Guyana’s gas program could, if linked to a clear renewable-integration plan, be framed as part of a credible energy-transition strategy rather than a fossil-fuel expansion. Such framing would help maintain investor confidence and broaden access to concessional or blended finance.

According to the ICMA Climate Transition Finance Handbook (2023) and the Climate Bonds Initiative Transition Criteria, gas projects can qualify for transition-labelled or sustainability-linked financing only where they demonstrably reduce lifecycle emissions and form part of a Paris-aligned, time-bound decarbonization pathway. Frameworks such as the EU and ASEAN Taxonomies similarly classify gas as a transitional activity when it replaces higher-emission fuels and supports renewable integration within defined emissions thresholds.

If Guyana’s gas-to-industry roadmap were structured within such frameworks, it could strengthen eligibility for sustainable-finance instruments while maintaining ESG credibility. This would tap into rising global investor demand for GSSS bonds (Green, Social, Sustainability and Sustainability‑Linked bonds). According to the OECD, the share of GSSS in Latin American sovereign bonds increased from 36 % in 2022 to 50% in 2023,17 reflecting a regional response to this growing demand. More recently, the Dominican Republic issued its first sovereign green bond in June 2024.18 Positioning the bond as a tool to help the country achieve its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) emissions reductions under the Paris Agreement boosted investor interest in the bond, which was six times oversubscribed, raising USD 750 million.

Pricing and Policy Will Define Outcomes

Turning Guyana’s gas potential into a sustainable onshore economy will depend on policy clarity, credible pricing, and execution discipline.

Policy and pricing will be pivotal. The government must balance its dual role as hydrocarbon stakeholder and policy-maker—seeking fair value for gas while keeping prices low enough to attract investment in power and industry. Unlike crude oil, which trades globally, domestic gas will be sold under a single negotiated price through shared infrastructure. Setting that price too high could deter investors; too low could weaken upstream returns. Transparent, balanced pricing will be central to maximizing national value.

Sequencing will also be critical. Prioritizing gas-to-industry and power projects that create a stable base of demand is critical for sequencing with the upstream developer. As each new floating production, storage and offloading (FPSO) unit comes onstream, available gas volumes will shift, making it essential to align field development with downstream project timelines. Synchronizing gas supply from successive FPSOs with the commissioning of industrial facilities would help manage volume risk and improve financing certainty for both upstream and downstream partners.

Governance and execution risks remain high. The ongoing delays at Wales 19 the importance of rigorous procurement, environmental oversight and experienced project management. Attracting bankable operators and creditworthy offtakers will be essential for both the LNG and gas-to-industry paths if Guyana is to translate its gas resources into economic value.

The analysis shows that while the government has options for gas monetization, the multipliers and social benefits of bringing gas onshore for industrial and power use, especially when combined with the major development projects of a road from Brazil, regional economic zone, and deepwater port, are transformative in comparison to the LNG alternative and have long-lasting impacts for the Berbice region and country overall.

SPONSORED BY:

References

Oil Now, ‘Gas-to-Energy pipeline mechanically completed, ready to introduce natural gas – Routledge’, October 2024

Demerara Waves, ‘Converting into liquefied natural gas not a priority – ExxonMobil Guyana’s chief’, October 2025

World Bank Group, ‘Understanding Natural Gas and LNG Options’, September 2017

Eni, ‘Eni celebrates the 100th cargo of LNG from Coral South FLNG’, April 2025

IEA, ‘Coming surge in LNG production is set to reshape global gas markets’, October 2025

GPL, ‘Development and Expansion Programme, Planning Horizon: 2023–2027’, December 2023

Guyana DPI, ‘Power ship now supplying 36 MW to national grid’, May 2024

EIA, ‘Guyana’, May 2024

IEA, Electricity 2024, May 2024

Guyana Times, ‘Design for deep-water port at Berbice being finalised’, October 2025

Kaieteur News, ‘Chinese firm wins bid to build Corentyne River Bridge’, December 2024

Stabroek News, ‘Guyana, state of Roraima to step up efforts for second phase of Linden to Lethem road’, July 2025

ITC, Trade Map, October 2025

Bureau of Statistics Guyana, ‘Guyana Labour Force Survey’, May 2021

Guyana DPI, ‘President Ali outlines bold diversification plan for sugar industry in second term’, June 2025

Reuter, ‘Guyana’s $1.9 billion gas-to-power project delayed to 2025', February 2024